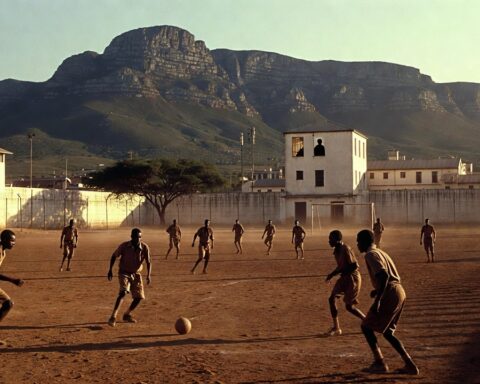

Football, eh? The so-called people’s game. The working-class ballet. A sport that once belonged to the terraces, to the lads and lasses who grafted all week, scraped together a few quid, and lived for that Saturday afternoon pilgrimage.

But now? Now, football has been lifted out of our reach, wrapped in silk and sold to the highest bidder, while the rest of us watch from the outside, noses pressed against the glass, trying to remember what it felt like to belong.

The Root of the Disease: How Did We Get Here?

It started slowly. Creeping, like damp up the walls of a crumbling council flat. In the 90s, the Premier League was born, a Frankenstein’s monster stitched together with TV money and corporate greed.

Sky Sports waltzed in with their satellite dishes and their glossy coverage, and suddenly football wasn’t just football—it was a “product.” And a product needs consumers, not fans. Consumers who can pay.

Ticket prices crept up. Clubs, smelling the money in the air, started refurbishing their grounds, slapping on new branding, and convincing themselves they weren’t just football clubs anymore—they were “global brands.”

They weren’t run by local lads who knew what a grafting wage looked like. They were run by suits who saw the working class as a liability, an inconvenient relic of football’s past. And just like that, the game started to slip through our fingers.

From the Terraces to the Boardroom: The Hijacking of a Culture

Back in the day, a football ground was a church. You stood shoulder to shoulder with your mates, singing, swearing, laughing, living. It was affordable, it was accessible.

Now? You’re lucky if you can get a seat without remortgaging your flat. Clubs have sanitized everything, replaced the soul of the terraces with prawn sandwiches and corporate hospitality.

Take Arsenal, for example. Once upon a time, Highbury was a fortress, a ground with character, with history. Then came the Emirates. Gleaming, modern, soulless.

And the ticket prices? Among the highest in Europe. £100 for a single matchday experience if you’re daft enough to buy a pint and a pie while you’re there.

Manchester United, Chelsea, Tottenham—all of them squeezing the life out of the fans who built these clubs from the ground up.

And then there’s the ticket resellers, the parasites feeding on the scraps. Want to see your team play in a big game?

That’ll be £300, please. Oh, you thought loyalty meant something? Think again, pal. Loyalty means lining the club’s pockets, year after year, while they pump out another hideous third kit and flog you a membership scheme that gets you absolutely nothing.

The Great Class Divide: Football’s New Elitism

Football was one of the last great social equalizers. It didn’t matter if you were skint, if you had a rough week, if the world was kicking you in the teeth—Saturday afternoon was yours.

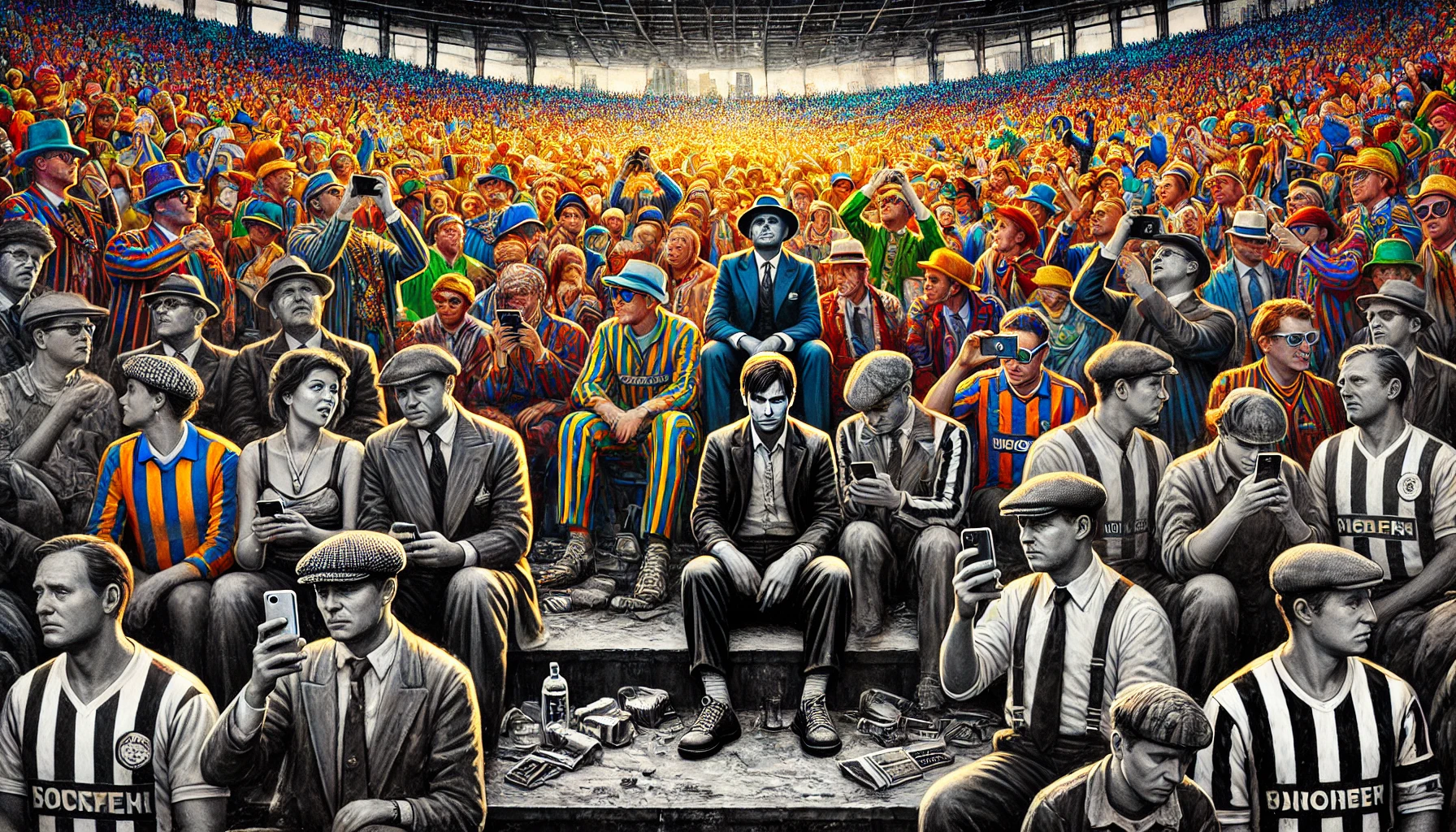

You could stand in the same ground as a bloke with a six-figure salary and know that, for ninety minutes, you were equals. That’s gone.

Football stadiums are now playgrounds for the wealthy. Clubs don’t care if a die-hard fan who’s been coming for 30 years gets priced out.

They’ll replace him with a corporate client who doesn’t even know who the left-back is but is willing to splash out on a VIP experience.

The game has become a tourist attraction, a sanitized spectacle for the well-off, while the real fans are forced into pubs or dodgy streams just to keep up.

And what happens when you push working-class fans out of football? You rip the heart out of communities.

Football was never just about the game. It was about the rituals, the camaraderie, the feeling of belonging.

It was about fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, passing down the love of a club through generations.

Now, kids are growing up watching their teams through a screen because their parents can’t afford to take them to a game.

And the clubs? They don’t care. As long as there’s a billionaire in a private box sipping champagne, everything’s grand.

The Wider Impact: Football’s Loss is Society’s Loss

You can feel it, can’t you? The disconnect. The way football doesn’t feel like ours anymore. We’re not supporters; we’re customers.

And if you can’t afford to be a customer, you’re not welcome. It’s the same disease that’s infecting everything—privatization, gentrification, the slow erosion of working-class culture.

Football is just another casualty, another thing that used to belong to us but has been stolen by those with deeper pockets.

The irony is that these clubs still trade on their history, their traditions, their “passionate fanbases.” They plaster images of old terraces across marketing campaigns, release retro kits, pretend they care about the working-class identity they’ve spent decades erasing.

It’s a con, a farce, a kick in the teeth to every fan who remembers what the game used to be.

What Can Be Done?

The fightback has begun. Across Germany, fans have fought tooth and nail to keep their game affordable. Safe standing, subsidized tickets, fan ownership.

They’ve held their clubs accountable, refused to be milked like cash cows. Meanwhile, in England, we’re still too polite, still too hopeful that maybe—just maybe—the clubs will listen. They won’t. Not unless we make them.

The answer? Walkouts, protests, refusing to play along with their greed. The clubs need us more than we need them.

Imagine an empty Old Trafford, an empty Anfield. Imagine fans uniting, refusing to be squeezed any further. It’s time to take back our game, to remind these clubs who they really belong to.

Because football isn’t about brand expansion, global markets, or corporate clients. It’s about us. It always has been. And if we don’t fight for it now, we might lose it forever.

Follow Me