Originally written in September 2019 by Alex Roberts

The players that enthrall us the most have always been the goal scorers. Defending is an art and there are few things as beautiful as a pinpoint 60-yard pass.

However, it’s the players who score which are hailed as heroes, especially in this digital, statistic-obsessed age.

That being said, it’s weird you’ve probably never heard of Josef Bican and his 805 competitive goals. Born in Vienna in 1913, Josef’s short life was about to change drastically with the outbreak of WW1.

His father, who was also a footballer, was lucky enough to come home unscathed but unfortunately, that is where his luck would run out.

He refused an operation on his kidney after picking up an injury during a game and it ultimately killed him.

Left to raise 3 children alone, Josef’s mother did the best she could. A single mother in the 1920s was afforded few opportunities, it was a male-led world and she couldn’t do much to stop the family from falling into poverty.

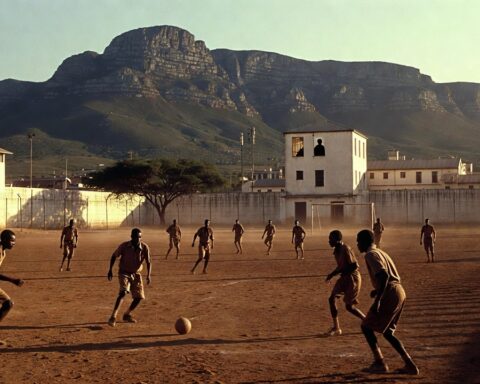

This didn’t stop young Josef’s love for football and it’s said that he continued to play in bare feet even when his family was unable to afford shoes.

Josef was eventually signed up to his first club at the age of 12, his father’s old and beloved, Hertha Vienna. Even at such a young age, the people could tell he was special.

One of the club’s sponsors being so impressed, offered to pay Josef 1 schilling for every goal he scored, with his family living in such poverty you can only imagine the kind of motivation this would give a young man who already had a knack for scoring, it makes you feel for opposition defenders.

Having made his full club debut at the age of 15 there was no stopping him. What happened to his father, however, remained fresh in the memory of his mother.

During a match she once ran onto the pitch to beat an opposition defender with her umbrella after and he tried his best to stop Josef by, predictably, kicking him across the pitch.

In time she gave up going to watch her son, a woman who had lost so much to the game, understandably, couldn’t take it anymore.

For a club like Hertha Vienna, a player like Bican was only ever going to pass through, and it happened just before his 18th birthday, Rapid Vienna, came calling.

Initially offered a poultry 150 schillings, Bican’s goal-scoring exploits forced their hand and they increased the offer to 600.

That may not sound like much compared to modern players but with football not really considered a ‘proper job’ at the time, an 18-year-old to be on that kind of salary was unheard of.

His 4 years at the club were goal-laden, an average of nearly a goal a game with 49 in 52 appearances didn’t go unnoticed and he became a pivotal part of the Austrian ‘Wunderteam’.

He’d play his only World Cup at the tournament’s inception in 1934. Being held in Italy during the 1930s, with the country under heavy fascist control, the first World Cup was wrought with controversy.

The Austrians were unfortunate enough to meet the Italians in the semi-final.

The game was of course fixed with the Swedish referee rumoured to have met Mussolini for a leisurely dinner the night before the game but I’m sure him awarding the game’s only goal, a goal where the ball, already in the keeper’s grasp, was pushed in by the Italian forward had nothing to do with that.

After the World Cup, Bican gained a move to city rivals Admira. This would be his final and least successful foray into Austrian football, with a meagre 18 goals in his 26 appearances.

He would not be afforded the time to become a legend at his new club. Growing political turmoil in central Europe would make him look outside of Austria for a new club for the first time in his career.

He left in 1937 and the Nazis took control in 1938. Czechoslovakia would be the country he chose to settle in, the country of his Father’s birth, and Slavia Prague, the lucky club to reap the benefits.

He would remain at the club for the next 11 years and play in Prague while Europe was burning during World War 2.

His talent was not enough to save him from the abuse he’d receive due to his Austrian heritage.

During his time at Slavia Prague he would fight for his image the only way he knew how, by scoring goals, managing to score 534 of them over those 11 years, including an incredible 57 goals in 24 games over one season.

He’d later distance himself even further from his Austrian roots by refusing to play for the ‘Wunderteam’ again and apply for Czech nationality.

His application was not to go through in time to play in the 1938 World Cup and the tournament lost one of the world’s stars.

The following year the Nazis invaded. After the war the super powers carved up Europe, and in 1948 an entirely different form of political upheaval would grab a hold of Czechoslovakia. Communism.

Bican’s days of playing tennis and lunching with movie stars were over. Playing for Slavia Prague, a club very much associated with the middle class put a target on his back.

He was offered to become a face for the ruling communist party KSC and its leader Klement Gottwald. True to form he turned down the chance to join the party.

Despite his humble beginnings, he was aware that he would have to work hard to change his image to protect his family.

He left Slavia in 1949 and joined Železárny Vítkovice, a club that was synonymous with the working class having been borne out of the steel industry and run by the steelworkers.

The goals kept coming, he managed to bag 74 in the 58 official matches for his new club and his image as a working-class hero was fully cemented.

Bican grew unsettled at the club and once again packed his bags and joined second division side Skoda Hradec Králové in 1952.

He wouldn’t have much time at his new club, only playing 9 times but managing to score 19 goals.

His hero status among the working class that he had worked so hard to regain ended up becoming a hindrance. On May 1st 1953 a routine communist propaganda parade was held.

A military convoy arrived and loudspeakers playing ‘Long Live President Zapotocky’ were met with yells of ‘Long Live Bican’ from the people.

This slight to the communist party did not go unnoticed and although it was no fault of his own Josef and his family were forced to leave the city within the hour.

It’s said that on their way to the train station, accompanied by two men in suits, they ran into a group of workers heading home for the day.

Worried about their star’s safety and the future of the club they loved they threatened a strike but Bican managed to talk them down.

It’s a good job too, Bican would have been sent to prison for 20 years for inciting a strike.

The prodigal son returned to Prague, where he spent his most successful spell rejoining Slavia Prague, renamed Dynamo Prague under communist rule.

In the last two years of his illustrious yet marred career, he’d score 57 more goals and become player-coach at the ripe old age of 42 before finally retiring.

Life after football was not easy for dear Josef. He’d manage several teams around the country but was never really able to call anywhere home.

The government made it hard for him to continue his lifestyle taking away many of the properties he had.

He would end up taking work as a roadside labourer almost falling into obscurity, until he got his lucky break.

Belgian fourth division side, Tongeren, were visiting in 1968 and Josef managed to impress them so much he was offered a contract to coach them. Taking them up from the fourth tier to the second during his time there.

Back home things were beginning to change for the better and in 1989 the velvet revolution would bring down the communist government.

Bican would return to Prague having had many of his properties returned and his name was reestablished as one of the greats.

He would remain in Prague until his death at the age of 88 in 2001, two weeks before Christmas.

A man of great principal with a love for the game that couldn’t be stopped by war and tyrants, I don’t think there is any man who deserves to be as well-known or well-remembered as Josef Bican.