Originally written in December 2019

To many, football in India might seem like a strange concept, but it has been prevalent for quite some time.

The country featured some interest from the late 1800s – 1970s, but India’s first major football league, the National Football League (NFL), was established in 1996.

Organised into 3 divisions, it hosted 10-12 teams during its lifespan until it was reintroduced as the I-League in 2007.

Designed to increase the pool of players funnelled into India’s national team, the I-League represented a huge step for India’s general production of players and mark on the map.

The aforementioned is one of two co-existing football leagues in India, with the other being the Indian Super League (ISL).

The latter has always been a franchise-based entity, with multiple sponsors and investors taking part in naming rights, league coverage, suppliers and revenues towards competition structure and corporate intake.

The I-League on the other hand, albeit also holding some of these attributes, has very much been the instigator for the attraction of foreign stars.

The criticisms of the leagues and the base of football in India are starkly financial. Unlike the ISL, clubs in the I-League rely on majority sponsors to fund their seasons; merchandise, ticket sales and TV revenue all goes to the All India Football Federation (AIFF).

With this being the case, clubs either just about get by on sponsor-income or place-winnings or they disband.

This was the case for four clubs which had to disband since the formation of the league, with exposure for clubs and the general sport in the country being cited as the main causes.

This is an issue, and it is clear that the leagues in India would benefit hugely from proper management of this.

One thing that has been done to push the love of football in the country very recently is the renewal of Star Sports’ contract with the English Premier League (EPL) until the end of the 2021/22 season.

This will show 250 EPL matches throughout each season and will show 380 live matches on its digital network, “Hotstar”.

As one of the biggest sports channels and sport-streaming services in India, there will be a larger percentage of the nation exposed to the sport once again.

Alongside this, the EPL also started up new official social media channels for both Instagram and Twitter in India, only strengthening the bond between the two nations and their footballing markets.

These are great steps, and ones I truly endorse. The perception that football isn’t big in Asia or India is incorrect, there are already hundreds of millions of people in India watching it.

The issue lies with turning that interest into playing and domestic ability and then turning that to success. Once doing so, attraction from inside and outside the country will come.

There certainly is a big market for football in India but nowhere near as big as it should be in terms of player development, productivity and attraction.

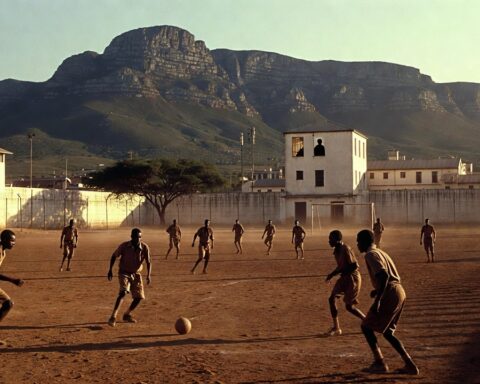

Now before we truly delve into this topic, I have to announce that my love of geography and geographical economics might shine through here, but I think they are pertinent points. Another big problem with India and its footballing market is infrastructure.

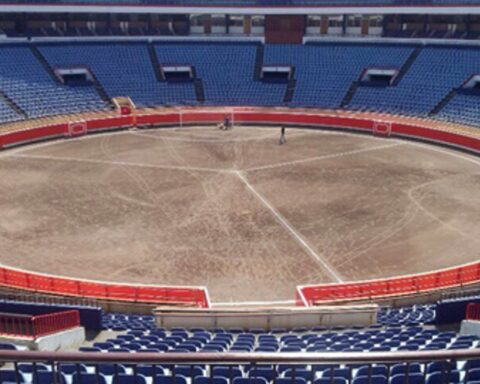

From stadiums to training grounds and their facilities within, India’s football system needs some work. Without these, player development becomes scarce.

The mere fact that many clubs cannot run their own stadiums or facilities as they are owned by the government or local councils is a root cause of the issue.

Take any club in the EPL and you really see what can happen when stable infrastructure and attraction are apparent; stadiums, facilities and general club business (on the whole) run smoothly. The infrastructure of clubs in the English top leagues are streets ahead of India.

For a nation that has a population of 1.37billion and a GDP (Gross Domestic Product) of $2.7 billion as of 2018 (statista.com, 2019) (which closely rivalled that of the UK at 2.8billion (knoema.com, 2019)), you would think the Indian government would funnel more into the infrastructure of football in its nation, being that it is the greatest sport in the world, right?

To solve the infrastructure issue, the government would have to increase its financial injection into the AIFF.

In a similar way to the Chinese development over the past decade, India will need to set themselves targets (provided the effort is made).

China set themselves a 2020 target of having at least 50 million people playing football and around 70,000 pitches available for them (Chadwick, 2017).

These ambitious targets are a great start, but there are many problems India would face in achieving these targets. India already has 7 major stadiums, the largest being “Salt Lake Stadium” with a capacity 85,000.

These were built for the 2017 U-17 FIFA World Cup, but if India were able to build upon this, there might be an increase in attraction for the sport via sponsors which would help generate money for domestic clubs etc.

In hosting events like this (which requires the necessary infrastructure) and setting targets like the Chinese have, there at least exists potential for even more growth. So much already exists, so why hasn’t anyone taken a real solid interest?

Football in India is seeing improvements in certain aspects. January 2018 saw India’s Men’s team achieve their highest ever FIFA ranking at 97th place mark.

Since then, India have see-sawed between 100th and 108th place in the rankings, currently sitting at the latter, either side of the Central African Republic and Kenya. The women’s team have also had contesting rankings and currently sit at 58th down one place since the summer of 2019.

However, there are positives for the national scene and women’s football in India generally.

India will host another tournament – the U-17 women’s FIFA World Cup 2020 and in early November of this year, Sports Minister Kiren Rijiju announced that sometime in December 2019, an all-new women’s football league would be constructed, an operation set to be “one of the most extensive football programmes in the country” (Press Trust Of India, 2019).

This is certainly a platform to build from as it is in collaboration with the Ministry of Women and Child Development, both important aspects to the country’s growth and internal wellbeing – two stages for great exposure not only with a rising youth population nationally, but worldwide too.

As women’s football continues its growth in the modern era, perhaps there are two markets that India could really exploit.

With this in mind, I do believe it is important to touch on the idea of youth moving forward. As mentioned above, India has an incredibly large population and there will be a projected 44.17% of the total population aged 1-24 (worldometers.info, 2019) in 2020.

With such a large youth population, there really does exist unimaginable potential to build a huge footballing base from the ground up.

Now what is apparent is that the national squad itself is of a fairly young age too, with the average age of the squad (including players having been called up in the last year) being 24.9 y/o; a stable age range and a mix of experience and youth. This is something India will have to build upon.

Encouraging, but as mentioned at the top of the article, the exposure of the sport domestically still needs work.

With around 630 million females in India by 2020 (iBid, 2019), projects like the one mentioned just above will really help to drive both male and female interest in football and hopefully create longer-lasting foundation moving forward. Culturally there may be a block though.

A report by the (BBC, 2017) stated that “of the 3,000 professional footballers in the English leagues, only 10 of them are British Asians”.

So perhaps culture has a stranglehold over the bridge between western sport and Asia, an issue deeply rooted in humanity perhaps?

For India themselves, certainly solving the financial and infrastructure issues would go a long way in developing players correctly and moving past that cultural block – turning young Indian-Asian footballers into real quality stars worth noticing.

Culture blocks had no part to play earlier this year though, where the EPL and the ISL teamed together to create a football development week in Mumbai. Around 40 youth players from Arsenal and Leicester City travelled to play against the youth teams of Mumbai City and Reliance Young Champs, alongside coaches and high-profile names such as Les Ferdinand.

Pushes for the improvements in refereeing, coaching and youth development will all benefit India’s foundation in sport.

EPL Director of Football Richard Garlick (2019) stated that “some promising young talent” was on show, and whilst a great feature, I feel this would be more beneficial as a stable facility rather than just a ‘feature-week’.

This for me is the reason why India is an untapped market, and why China has seen a surge in development of its football market.

What China and President Xi Jinping have done is show ambition, especially when considering programmes and centres such as Guangzhou Evergrande’s youth academy, which houses around 50 pitches and 2,500 students (Kenmare, 2019) all aged 9-18, designed to offer training, study, development and education in the form of a free scholarship-based system (Huang, 2018).

India need the investment and ambition to match, and they’re certainly capable financially.

Now, in a way India’s footballing market is one that is being tapped, but at a considerably less rate than it should be, given all that we’ve discussed in terms of population, finances and youth.

The issues that have been highlighted certainly aren’t easy ones to overcome but there are simple solutions to making those hurdles easier to jump.

India’s footballing market is one that has made great strides over recent years, and although does continue to, there is so much more to be done in terms of the infrastructure of the leagues, clubs and development of players and staff.

The financial aspects of both the government and the clubs themselves also needs to be addressed as the potential for a flourishing partnership between the AIFF and the government really exists. Really great work so far, but there’s much more to do.

Football in India truly is the tapped market that remains untapped.

References

BBC (2017), “Son challenges dad: Why couldn’t I go to Man Utd trial?”. BBC News: England. Accessed: (9th December 2019). Found at: [ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-england-birmingham-41428071/son-challenges-dad-why-couldn-t-i-go-to-man-utd-trial ]

Chadwick, Simon, (2017), “Why realising China’s grand football plans will require much more than money and policy”, South China Morning Post, South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. Accessed: (27th November). Found at: [ Accessed: (27th November). Found at: [ https://www.google.co.uk/amp/s/amp.scmp.com/sport/soccer/article/2078080/why-realising-chinas-grand-football-plans-will-require-much-more-money ]

Garlick, Richard (2019), “Football Development Week in India a success”, Premier League.com, Premier League:: Youth. Accessed: (7th December). Found at: [ https://www.premierleague.com/news/1087478 ]

Huang, Andrea (2018), “Evergrande Football School launches new free program to recruit players 9-18 years old”, Yutamg Sports: Industry News: Within Chinese market: Football: Sport companies, Yutang Sports (Beijing) Co., Ltd. Accessed: (11th December 2019). Found at: [ http://mobile.ytsports.cn/news-4570.html ]

Kenmare, Jack (2019), “A Look At The World’s Largest Soccer School: Guangzhou Evergrande’s Youth Academy”, Sport Bible, Football, sportsbible.com, LADBibleGroup. Accessed: (11th December 2019). Found at: [ https://www.google.co.uk/amp/s/www.sportbible.com/football/news-reactions-a-look-at-the-worlds-largest-soccer-school-guangzhou-evergrande-20180327.amp.html ]

Knoema.com, (2019), “Gross domestic product in current prices”. United Kingdom, economy: 2018. Accessed: (26th November). Found at: [ https://www.google.co.uk/amp/knoema.com/atlas/United-Kingdom/GDP%3fmode=amp ]

Press Trust Of India, (2019), first post.com, “Sports Minister Kiren Rijiju targets football movement in India with first-ever women’s league to be launched next month”, Firstpost. Accessed: (30th November)z Found at: [ https://www.firstpost.com/sports/sports-minister-kiren-rijiju-targets-football-movement-in-india-with-first-ever-womens-league-to-be-launched-next-month-7592011.html ]

Statista.com, (2019), “Gross domestic product (GDP) in India 2024”, India: Gross domestic product (GDP) in current prices from 1984 to 2024 (in billion U.S. dollars): 2018. Accessed: (26th November). Found at:[ https://www.statista.com/statistics/263771/gross-domestic-product-gdp-in-india/ ]

Worldometers.info (2019), “India Demographics”, Population by Broad Age Groups (2020). Accessed: ( 26th November). Found at: [ https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/india-demographics/ ].