By the time the sun hit the tops of the Balkan mountains, you could feel the chaos brewing. Bulgaria in the late ’80s was a swirling cauldron of smoky bars, backroom deals, and a government teetering on the edge of collapse.

Somewhere in that maelstrom of concrete and desperation, a young, feral footballer with a chip on his shoulder the size of Mount Vitosha was sharpening his fangs.

Hristo Stoichkov—a name that rolled off tongues like a grenade pin being pulled—was a creature born not of privilege but pure, unfiltered rage. To understand Stoichkov is to understand a man who played football like it was a battlefield, a gladiator who treated the pitch as his personal Colosseum.

He was no mere athlete. He was a bloody hurricane wrapped in cleats, charging through life with the finesse of a charging bull and the temper to match.

Born for Fire

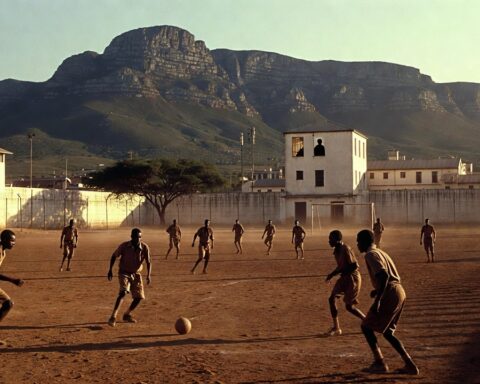

Stoichkov’s story begins in Plovdiv, a city where the air smells faintly of history and cheap cigarettes. His early days were spent dodging poverty and authority figures, kicking anything vaguely spherical.

Football wasn’t just a pastime for young Hristo; it was an escape hatch from a system designed to crush spirits like soda cans.

He wasn’t the biggest or fastest kid, but his instincts were otherworldly. A predator’s nose for the ball, an artist’s touch when he wanted it, and—most importantly—a volcanic temper that could turn the most disciplined defenders into quivering wrecks.

By the time he landed at CSKA Sofia, Stoichkov was already an outlaw in the making. If you weren’t terrified of him, you didn’t understand what you were dealing with.

The Rise of The Dagger

In 1989, Stoichkov etched his name into Bulgarian folklore during the Bulgarian Cup final, a match that ended in an all-out brawl so feral it would have made Roman gladiators blush. Suspensions, fines, and accusations flew like bullets, but Stoichkov emerged unscathed—his reputation as a bad boy fully cemented.

This was Hristo in his natural state: chaos incarnate. It was less about winning and more about making sure everyone in the stadium left knowing they’d just witnessed a man who would eat broken glass for breakfast if it meant getting the ball in the net.

Over five years with CSKA Sofia, Stoichkov racked up 81 goals in 119 league appearances, a staggering strike rate that marked him as one of Europe’s deadliest forwards. He also helped the team secure three Bulgarian league titles and four Bulgarian Cups. These achievements, however, were just the prelude to a much grander saga.

By the time FC Barcelona came calling in 1990, Stoichkov was already a national hero, the embodiment of Bulgaria’s defiance. He was brash, unapologetic, and fully aware of his talent—a Molotov cocktail hurled at the pristine halls of European football.

Cruyff’s Wildcard

Barcelona in the early ’90s wasn’t just a team; it was a symphony conducted by Johan Cruyff. The Dutch maestro’s philosophy was a religion, and every player was expected to adhere.

Then came Stoichkov, the living antithesis of discipline. But Cruyff, the sly fox, knew what he had. You don’t put a muzzle on a wolf—you let it hunt.

Stoichkov tore through La Liga with the precision of a sniper and the fury of a berserker. His partnership with Romário was less a tactical masterclass and more a rampage—two volatile geniuses running riot over defenders who looked like they’d rather be anywhere else.

Between 1990 and 1995, Stoichkov scored 76 goals in 151 league appearances for Barcelona, becoming a cornerstone of Cruyff’s “Dream Team.”

During his tenure at Barcelona, Stoichkov won five La Liga titles, the Copa del Rey, and—most significantly—the UEFA Champions League in 1992. His performances in European competitions were particularly ferocious, scoring 21 goals in 38 UEFA Champions League matches during his career.

Stoichkov’s fiery personality also made him the heart and soul of the team, though it occasionally led to clashes with opponents, referees, and even teammates.

By 1994, Stoichkov was at his apex, claiming the Ballon d’Or after leading Bulgaria to the semi-finals of the World Cup. His six goals in the tournament tied him for the Golden Boot, as he almost single-handedly dragged his team through a gauntlet of more established footballing nations.

Stoichkov scored crucial goals against Argentina and Germany, each celebration a declaration of war.

It was during that summer in the United States that the world saw Stoichkov in full bloom. He wasn’t just playing football; he was waging psychological warfare.

Every goal was a manifesto. Every celebration was a middle finger to anyone who doubted him. Bulgaria’s improbable run was fueled by his madness, and his face became the symbol of a nation no longer content to sit in the shadows.

The Flaws of a God

But no flame burns forever. By the late ’90s, Stoichkov’s career was winding down, and the cracks in his mythos were impossible to ignore. He’d burned too many bridges, kicked too many shins, and screamed at too many referees.

His temper, once his greatest weapon, became a liability. The genius remained, but the chaos no longer inspired awe; it just tired people out.

After leaving Barcelona in 1995, Stoichkov had stints at Parma, Al-Nassr, and later returned to CSKA Sofia. While his raw talent still flickered, his best years were behind him. Even so, he managed to rack up a total of 308 career goals in 680 matches—an impressive tally that cemented his status as one of the greats.

His later years were a patchwork of coaching stints, punditry, and the occasional scandal. Stoichkov’s personality never softened. Age did not mellow the beast. If anything, it made him even more cantankerous—a man forever locked in a battle against mediocrity, stupidity, and authority figures.

Legacy of the Mad Dog

Hristo Stoichkov’s name still sparks debate over rakia and long Balkan nights. To some, he was a hero, a man who dragged Bulgarian football onto the global stage with his bare hands. To others, he was a walking calamity, a reminder that talent without restraint can be as destructive as it is glorious.

But one thing is certain: Stoichkov lived and played on his own terms. He was a man who refused to bow, even when it might have been wise to do so. And in a world that increasingly values conformity and polished perfection, that might just be his greatest legacy.

As I sit here with a half-empty bottle of something flammable, trying to make sense of the myth and the man, I can’t help but smile. Stoichkov didn’t just play football. He was football—beautiful, chaotic, and utterly unforgiving. May the Mad Dog of Sofia never be forgotten.

Follow Me